A recent study of total economic costs in Europe found wide variations, in part due to differing definitions, methods and data sets.

By Andrew Boada, Editor at Large

Building a business case for new fleet safety initiatives hinges on a single piece of data: the cost of the average crash to employers. In the U.S., fleet managers have a ready-made number: as of 2015, it’s $24,057. But what about the rest of the world?

As far as Fleet Management Weekly has been able to determine, no such number exists for any other country. What we have found, however, is a 2016 study on the total economic costs of all traffic accidents for 31 countries in the European Union and Western Europe. While a good start, the authors admit that there’s such variation in how each of the countries calculates the cost of accidents and defines injuries that their numbers aren’t fully comparable. A second shortcoming of the report is that the numbers include costs that aren’t borne by employers, like lost lifetime household earnings and the cost of emergency services.

Nevertheless, it’s worth global fleet managers’ while to know what the report does say, and how those costs stack up against the U.S. numbers. So, let’s start with the U.S. figures, derived in a study jointly sponsored the Network of Employers for Traffic Safety (NETS) and the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

Here are the broad strokes of that study: a property-damage-only accident – where only sheet metal suffers – costs, on average, $5,890. The average accident that results in a non-fatal injury, the study found, cost employers more than 10 times that sum, or $64,981. Worst are those that result in a fatality: $671,515. All up, the average crash costs a U.S. employer $24,057.

It’s important to recognize that those figures include a number of “hidden costs” of accidents that don’t cross a fleet manager’s desk but affect every organization’s bottom line. These include such expenses as lost productivity, increases in workman’s compensation and health insurance premiums, the cost of recruiting and training new employees to replace those permanently lost, general administration and legal costs, and liability, to name several.

Knowing that, it’s not unreasonable for a U.S. fleet manager to argue that preventing 100 accidents could save an employer $2.4 million a year, and an investment of, say, $1 million would achieve a very attractive net return on investment of 140 percent.

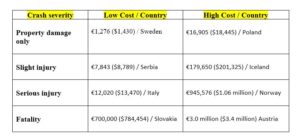

The figures we found for European crashes come from a 2016 study titled Crash Costs Estimates for European Countries, by a team of researchers from seven countries, led by Wim Wijnens of the Dutch Institute for Road Safety. Across four levels of severity the study found a remarkably wide range of crash costs by country, as shown in the table below: [click to enlarge]

(To see the full report and a full list of costs by country, visit https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/bitstream/2134/24949/1/D32-CrashCostEstimates_Final.pdf)

Compared to the U.S. study, the most glaring shortcoming here is the lack of a single “average” accident cost. Perhaps the most reliable figures for global fleet managers’ calculations are those for property-damage-only crashes. Unfortunately, the report offers no explanation for how widely they vary.

As for the others, the study attributes the variations to the makeup and categories data different countries collect and report, as well as how they define injury levels and deaths caused by crashes (some countries limit the time between a crash and death – beyond a certain number of days, the crash isn’t considered the cause). To the report’s credit however, it does take into account such “hidden” crash costs as lost productivity, the cost of insurance and costs associated with recruiting and training new employees.

So, at Fleet Management Weekly, it’s our view that these findings are of limited use to fleets. And, in fact, one of the authors’ conclusions is the serious need for European countries to harmonize how they calculate crash costs. We’d also add that to render the numbers most useful to fleet managers, costs they don’t incur – like those for lifetime household lost income, degraded quality of life, and the costs of emergency services – should be subtracted.

But we don’t think global fleet managers should leave it at that. The business case for new investments in safety still needs to be made, and that requires data. Perhaps – if they’re not already at it – global managers ought to ask their country managers to gather the missing information — lost productivity, higher insurance premiums and the like – on their own.

Only then can they set a value on the expected reduction in accidents and compare it to the new money they’re asking for. If the experience of U.S. fleet managers is any gauge, the return on investment should be impressive.

Browse previous Globally Speaking columns